By Payam Mohseni and Mohammad Sagha*

Since the turn of the century and the increased global focus on the Middle East and Muslim world, many scholars have been quick to recognize the wide gap of knowledge and understanding of Islam in the West, including in the United States. While some progress has been made in better understanding the religion, when it comes to cultural and social diversities within Islam, we see the major ongoing recurrence of problematic generalizations and misunderstandings regarding the two major sects of Islam (Sunnism and Shi’ism) as well as sectarianism in the Muslim world. These problematic narratives pervade mainstream analysis on the Middle East and posit, for instance, a rigid and eternal “Shi’a-Sunni” divide that subsequently is behind conflict in the region. This elementary understanding—that there exists different sects and denominations within Islam– thus can and does feed into false and simplistic narratives of ancient sectarian violence within the Islamic world.

Behind these problematic narratives on sectarianism are a series of questionable assumptions or simplified explanations regarding Islam, the Middle East, and religious identity. By “sectarianism” we refer to the privileging of one’s sect or confession within a religious tradition and/or ultimately accepting a particular confessional reading of religion as the true reading of that religious tradition. In this article, we look to address and critique five of the top “myths of sectarianism” within Islam in the Middle East in order to produce analytical clarity and inform debates for scholars, policymakers, and religious leaders concerned with these issues. This is important in order to theorize pathways for sectarian de-escalation and to try to reduce harmful exclusionary sectarian practices and beliefs in the region which have increased dramatically in recent times.

Myth One: Shi’as and Sunnis have been involved in a millennia-long religious war and are inherently disposed to violent conflict

The Muslim world is vast, diverse, and has a long history that includes significant experiences in peaceful co-existence between different Muslim denominations. Throughout time, significant sectarian fluidity existed among Muslims in what can be described as “confessional ambiguity,” where Muslims openly combined what are today considered discrete aspects of Shi’a and Sunni doctrine and authority structures. Furthermore, in varying contexts of peace and violence across the centuries, there has been diversity in the sectarian affiliation of ruling Muslim dynasties across the Islamic world with both Shi’as and Sunnis ruling over diverse Muslim (and non-Muslim) denominations that were not necessarily affiliated with the ruling Muslim sect.

Communal relations between Shi’as and Sunnis are therefore dependent on historical context. The nearly 1,400-year history of Islam reflects a history of peaceful relations mixed with violence and the various power dynamics which color relations between different Islamic sects and ruling dynasties. While mainstream narratives portray a war-prone history with politicians like President Barak Obama having stated that in the Middle East, “the only organizing principles are sectarian” – and that these sectarian disputes “date back millennia” – the reality is more complex and context-dependent than broad strokes which portray as ancient and perennial sectarian conflict within Islam. The Sunni-led Ottomans and the Shi’a-led Safavids did engage in several destructive wars in the middle periods (ca. 16th – 18th centuries) when more identifiable sectarian demarcations were institutionalized, but sectarian relations between Sunnis and Shi’as are by no means limited to such bouts of imperial conflicts. All the great Persian poets of the middle periods (Rumi, Hafez, Attar), for example, are claimed by both Shi’as and Sunnis alike due to their confessional ambiguity and are loved across the religious spectrum. Two of the founders of the “Sunni” schools of law, Abu Hanifah and Imam Malik, studied under the sixth “Shi’a” Imam, Ja’far al-Sadiq, and countless other examples demonstrate the fluid and mainly peaceful relations between Muslims of all stripes which was more often than not the norm throughout Islamic history.

Myth Two: Sectarian violence in the Middle East is primarily between Sunnis and Shi’as

While many actors in the Middle East including Sunni and Shi’a majority states and militias use religiously sanctioned violence against their adversaries, the growth in modern sectarian violence cannot be properly understood as a blanket “Sunni-Shi’a” dynamic, but is instead largely driven by the significant rise of a separate phenomenon: militant Wahhabism. At its core, the unprecedented spread of takfiri ideology (i.e. to excommunicate or anathematize opponents) found within radical Wahhabism is largely responsible for doctrinally legitimating violence towards the “Other” and has been as problematic within the larger Sunni community as it has been for Shi’as and other minorities in the region. By considering sectarianism fundamentally a product of Sunni-Shi’a disputes, such rhetoric downplays and minimizes the major violence committed against Sunnis by Wahhabis, reifies “Sunni radicalism” as a category, and misidentifies sources of conflict in the Middle East.

The Wahhabi movement is rooted in the Arabian Peninsula, originally emerging in the 18th century and today forming the bedrock of the clerical authority in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Wahhabi radicalism that feeds in to groups such as ISIS and al-Qaeda – known primarily in mainstream media for terrorism – and confronts Sunnis, Shi’as, Christians, Jews, Yazidis, and others alike, is the most responsible in terms of scale and impact for spreading violent sectarian beliefs and practices such as the enslavement of women (both Muslim and non-Muslim) within the Islamic world. Sectarianism indeed undergirds and goes in hand with radicalization and terrorism. According to analyses utilizing the University of Maryland’s Global Terrorism Database, the vast majority of deaths inflicted by Muslim terrorists since 2001 were undertaken by al-Qaeda, ISIS, and other like-minded groups[1]—radical Wahhabis, in other words. It is of course important to note that the pro-monarchical Wahhabism of Saudi Arabia is also threatened by other Wahhabi militant groups such as ISIS who oppose the Saudi royal family and its ties to the United States, demonstrating some of the fractious internal rivalries within contemporary Wahhabism itself.

Of course, this is not to trivialize other manifestations of sectarianism or to claim that Saudi Arabia or radical Wahhabis are solely responsible for all sectarianism in the Middle East – states such as Iran, Turkey, and the UAE (as well as others) can and do instrumentalize sectarianism for state interests. However militant Wahhabism stands alone in its doctrinal and often genocidal beliefs and actions towards the sectarian Other. In Iran, for example, privileging of contemporary Twelver Shi’a identity and doctrines are enshrined in the constitution through defining the Islamic Republic as a placeholder government for the Twelfth Imam, and the state unofficially prevents sensitive government positions from being occupied by Sunnis or non-Shi’as. Iran’s support for regional Shi’a militias also represents in part a sectarian strategy which at a minimum negatively bolsters sectarian narratives and threat perceptions of a rising Shi’a threat by certain Sunni communities. In Turkey, longstanding state discrimination against Alevi places of worship and civil status laws exist which have created tensions between different religious communities, and the Turkish state has been quite active in supporting various militias with explicit sectarian motives in Syria. In Iraq, sectarian violence has a long history under Saddam Hussein, but violence continued following the 2003 U.S. invasion when the Shi’a “Mahdi Army” affiliated with Muqtada Sadr began a campaign of indiscriminate killings of Sunnis in Baghdad and beyond following al-Qaeda’s devastating 2006 bombing of the al-Askari shrine in Samarra which hosts the tombs of important Imams.

Importantly, although the Wahhabi movement self-identifies as “Sunni” – and Western mainstream analysis commonly frames geopolitical contestation in the Middle East to be between “Sunni Saudi Arabia” and “Shi’a Iran” – Wahhabism’s place within the Sunni community has always been an ongoing source of contestation (and even violent conflict). This is largely due to Wahhabism’s rejection of basic tenets of mainstream Sunni Ash’ari theology, which today largely rejects carte-blanche excommunication and sanctioned violence on practicing Muslims. Looking at some of the major conflict zones in the Middle East, whether in Syria or Yemen, for example, we observe a “Wahhabi-Shi’a” conflict more so than a “Sunni-Shi’a” one– and in fact we also witness a simultaneously intense “Wahhabi-Sunni” conflict including against Sufi-oriented Sunnis or even secular or mainstream Sunnis in those same places. While sectarian identity of course pervades much of the activities of non-Wahhabi Muslim actors (Sunni and Shi’a alike) in conflict zones in the Middle East, these other actors generally do not aim to wipe out the sectarian Other, systematically target Christians or other minorities and enslave their women and children, or programmatically destroy religious and historical monuments and houses of worship as carried out by radical Wahhabi groups.

This points to the importance of understanding how the single concept of sectarianism can be used and applied differently to various sects and actors within the Islamic community. The importance of the monumental Amman Message of 2004 was a noteworthy affirmation of inclusive orthodox Islam and a clear rebuke of takfiri excommunication ideology. This message, which affirmed diverse Muslim practices and beliefs as acceptable within Islam, was signed by the most high-ranking and popular representatives of nearly the entire Muslim world’s denominations, showcasing mainstream Sunni, Shi’a, and Ibadi solidarity against takfirism as a leading problem in contemporary Islam. It is also important to note that the phenomenon of sectarianism can take on different forms across different regions. In South Asia, for example, there are different layers and dynamics to sectarianism both between Sunnis and Shi’as but just as importantly among different groups of Sunni revivalist movements and Sufi orders (i.e. between Deobandis, Ahl-i Hadith, Barelvis, etc.)—especially in a context where Wahhabism has a different foothold than in the Arabian Peninsula and the Middle East. Further research can help elucidate these diverse patterns and sub-strands that sectarian identities and sectarian behavior can take across world regions and even in particular localities.

Myth Three: Sectarianism is really just about politics

More sophisticated analyses which look to move beyond simplistic religious or sectarian generalizations focus on the primacy of “politics” in driving conflict in the Middle East and tend to downplay or ignore religion altogether as a relevant factor. While it is tempting to attribute sectarian conflict in the Middle East solely on “politics” and discard with the admittedly problematic use of religion and sect-based narratives so dominant today, ignoring the very real and independent role that “religion” plays can itself undermine our understanding and explanations for what is going on in today’s Middle East. In other words, sectarian thought and ideology cannot simply be reduced to tools in the hands of state powers to further their interests. While religious doctrines and beliefs can of course be manipulated by state actors who ascribe to different ideologies, it is only because religious ideology is an important individual driving factor in believers’ lives and has its own idiosyncratic content that can be used in unique ways by state powers who are looking to instrumentalize these beliefs for their own benefit.

For example, it is not possible to boil down contemporary Shi’ism in the Middle East simply as a function of Iranian politics, whether considering diverse Shi’a political parties and movements in the region as seen in Iraq, Lebanon, Yemen or beyond, or even considering historical and theological ideas such vilayet-i faqih (the ideational basis of the modern theocratic system in Iran) which is a content-based phenomenon stemming from Shi’a thought and doctrine and cannot be understood as simply an instrumental political action that emerged from state actors. Likewise, it is not sufficient to simply reduce the complex challenge of militant takfirism to the policies of a state and ignore the unique ideological nature of Wahhabism itself. Wahhabism in other words is also a theological issue when it comes to violent sectarianism, just as it is an ideological challenge (not simply political) within mainstream Sunni theology and the broader umbrella of Sunni religious thought.

Furthermore, on a more fundamental level, conceptually disentangling “religion” from “politics” is no easy task and it is an open question in the field whether such a particular division is indeed even useful – especially given that Islamic political thought generally does not carry such an internal secular vocabulary which clearly demarcates politics and religion. The conceptual line between religion and politics is notoriously blurry and by explaining away the role that religious commitments and ideology can play in driving behaviors on the ground, analysts can misidentify drivers behind phenomena such as sectarianism. Taking seriously the nature, ideology, and impact of religious thought is necessary to broaden our understanding beyond what we may commonly understand as the political. From incorrect analyses which failed to predict the victory of the Iranian Islamic revolution, to post-2003 Iraqi politics which witnessed a resurgence of Islamist mobilization, to the pervasive Islamic revivalism in Turkey and the entrenchment of the ruling AKP, misunderstandings regarding the nexus between religion and politics has led to serious shortcomings in explaining significant contemporary phenomenon and major social trends.

Myth Four: The United States is not involved in intra-Islamic disputes in the Middle East

While it is a common refrain of U.S. policymakers across both parties that the United States is not interested in getting involved in an intra-Islamic “sectarian dispute” that supposedly stretches back time immemorial, the United States is in fact deeply involved, directly or indirectly, in sectarian dynamics in the Muslim world. The United States effectively changed the balance of power in the Middle East by toppling Saddam Hussein in 2003, which led to democratic elections bringing to power a Shi’a majority government in Iraq for the first time in centuries in what was a clear boon for the region’s Shi’as and Iran. This points to indirect consequences for sectarianism that U.S. actions hold on issues of foreign policy which may be unrelated to sectarian considerations in the first place. Indeed, as asserted by American diplomat Peter Galbraith, on the eve of the 2003 invasion of Iraq, former President George W. Bush invited three leading Iraqi exile figures to watch the Superbowl with him and in the ensuing conversations was completely unaware about the differences between Shi’a and Sunni Muslims in Iraq.

On the other hand, the United States’ alliance with Saudi Arabia, as its primary Arab ally in the region, has serious consequences for perceptions and realities of U.S. involvement in the larger Middle East. Namely this relationship signifies an uncomfortable acquiescence of the Wahhabi religious establishment that grants the Saudi monarchy its ruling legitimacy, as the very pillars of the Kingdom rest on its centuries-long historical alliance with the Wahhabi clergy. This can become particularly problematic and misrepresent American values given our carte-blanche support to Saudi Arabia’s foreign policy objectives with little to no accountability. Such dynamics negatively shape perceptions on sectarianism and feeds into grievances that the United States is taking sides in intra-Muslim affairs via its alliance with Saudi Arabia which is leading a devastating war in Yemen (with U.S. support), supported a crackdown in Bahrain against the Shi’a majority populace during the Arab Spring, and is involved in discrimination against Shi’a Muslims residing in the Kingdom, among other critical policies in the region.

Negative perceptions regarding the U.S.-Saudi alliance also not only increase anti-American sentiment among mainstream Sunnis and Shi’as who are on the receiving end of violence committed by Wahhabi groups, but also, ironically, further deteriorates the U.S. image among radical Wahhabis who are virulently anti-American (as well as opposed to the Saudi monarchy and its alliance with the United States). Therefore, the special nature of the U.S.-Saudi alliance radicalizes anti-American sentiments across the spectrum while simultaneously harming U.S. relations with other Muslim actors and current and potential partners in the Middle East. The Saudis and Wahhabi establishment are also staunchly opposed to rival Sunni political movements which have pitted them against the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt and Turkey as well as against other forms of Sunni political Islam (especially those combining Islam and elections) which has strained U.S. relations with its other traditional allies in the region. It would be wise if the United States, in pursuit of its strategic objectives and national security interests, pursued a more balanced approach with a multitude of diverse actors in the region instead of relying almost exclusively on Saudi Arabia.

Moreover, this situation can create important challenges for a core U.S. policy objective in the Middle East – combating terrorism – given that Saudi Arabia shares ideological roots with the very groups the United States is committed to eliminating. This is particularly pertinent when considering the intimate relationship between terrorism and sectarianism in which many of the top terror groups (ISIS, different al-Qaeda branches, etc.) are at the forefront of sectarian atrocities and spreading sectarian hate-speech. These implications regarding sectarianism should not be easily ignored by U.S. policymakers and analysts as they deeply influence popular and elite opinion of American actions and policy effectiveness in the Middle East.

Myth Five: Sectarianism is necessarily bad and violent

Sectarianism is the belief or practice of a particular interpretation of religion as the ultimate true interpretation and privileged practice of that religious tradition or identity. By itself as a concept, it thus does not necessarily have to hold positive or negative connotations as commonly perceived. Shi’ism and Sunnism, for example, are two sectarian readings of Islam – that does not make them necessarily violent or destructive. Sectarian readings are an intrinsic part of any religious tradition and reflect the plurality of interpretations that accompany all religions. These readings include different legal methodologies, various theological readings of Islam, and diverse ritual practices within and across Sunnism and Shi’ism. Most of the confessional differences within Islam are negligible and the Muslim world is surprisingly uniform with generally minor variation in its religious beliefs and practices (e.g. daily prayers, core doctrines, pilgrimage to Mecca, etc.).

Our task as scholars and practitioners should be to differentiate between harmful exclusionary sectarian thought and practice rather than the sectarian pluralism that goes hand in hand with religious diversity in the Muslim world. In other words, our goal should not necessarily be to encourage Muslims to eliminate or resolve different sectarian points of view but rather to eliminate those destructive and harmful aspects of sectarianism. This is relatively a feasible track to undertake, unlike resolving sectarianism writ large. By employing the term “sectarian de-escalation” we mean processes that lead to acknowledgement and respect for diverse interpretations of Islam which are natural to any religious tradition, and eventually to “sectarian appreciation” and the recognition of benefits to diversity. This, we hope can encourage the expansion of pluralistic spaces in which Muslim denominations can peacefully co-exist and grow alongside one another, while identifying and eliminating the harmful sectarian factors that can lead to escalatory violence, persecution, and unjust discrimination.

Conclusion

The main conclusion from the above discussions is to complicate any single “grand sectarian narrative” whether it is the Iran-Saudi Cold War, the Shi’a-Sunni primordial identity thesis, or other sweeping macro-framings of geopolitical events or religious trends in the Middle East and Islamic world. Instead, each case involving sectarianism must be investigated in its own context which vary according to the specific ideational contents of each religious tradition, historical and social dimensions, regions, legacies of empire and state building, and other relevant factors. As our discussions of sectarianism in the Middle East demonstrate, many of current mainstream analytical narratives problematically approach Muslim politics through the lens of perennial ancient inter-sectarian wars and other anachronistic frameworks of “Shi’a-Sunni” divisions or even “Persians vs. Arabs.”

Such rhetoric was used excessively even by secular Arabist dictators such as Saddam Hussein during his reign in order to brand the Arab Shi’a opposition to him as a Persian threat to true Arab identity (and by extension “orthodox Sunni Islam”) – pointing to the fact that it is not just “religious” actors producing and reinforcing sectarianism in the region. In the Arab world, one of the added complications of using nationalist rhetoric in order to shift emphasis away from religious sectarian identity is the legacy of Arabism which conflates ethnic Arab identity with a national one. This Arabism is usually framed in anti-Persian and anti-Shi’a rhetoric as seen under both Saddam Hussein’s rein as well as some strands of contemporary Iraqi nationalism and the way that many Arab neighboring states exclusively emphasize shared Arab heritage as the basis of political and diplomatic cooperation with Iraq as a means to drive a wedge between Iraq and Iran. The broad applicability of sectarian language and its ubiquity in the Middle East unfortunately often regularly seeps into the rhetoric of journalists and policymakers as well.

In reality, sectarianism is a much broader and nuanced phenomenon than a blanket “Sunni-Shi’a” dichotomy; indeed, there are often more important intra-denominational dynamics and contestation within sects than between them which are embedded in complex regional geopolitics and interstate competition. In the Middle East—the regional focus of this article—a more accurate survey of sectarianism would greater emphasize the impact of Wahhabism on sectarianism, but on a more global scale recognize regional diversity and the particularity of overlapping yet still distinct geographic zones across the Middle East, Central Asia, and South Asia, for example where sectarian relations do not fit into a uniform analytical mold and have differing dynamics. Institutional and social variety within Islam and particularly within the vast umbrella of “Sunnism” is quite vast and diverse which requires much greater nuance when discussed as a category within scholarly and journalistic works.

As long as Islam as an identity, generic marker, or practice is relevant in the lives of Muslims, confessional and sectarian pluralism will continue to be relevant as well – as is the case for any global religion for that matter. This is because diversity and sectarian readings of Islam are embedded as normative practices within the religion itself which can take on both positive and negative aspects depending on the given socio-political circumstances. This religious diversity is quite difficult to generalize into easy categorizations and moves beyond the geography of the Middle East, especially as the majority of Muslims in the world reside outside this region. Studying “sectarian violence” in particular requires the use of more accurate terminology and understanding of sectarianism as a concept. As such, we emphasize the necessity for scholars and analysts to undertake rigorous interdisciplinary and theoretical engagement with the concept of sectarianism in order to explore the best peace-building initiatives moving ahead. This endeavor should also take seriously the diversity of religious groups across Muslim denominations to reach a more nuanced and accurate understanding of sectarian dynamics and politics in the Middle East.

In recognizing the complex and varied ways that sectarianism can express itself, the call to “sectarian de-escalation” therefore refers to a project not aimed at diminishing Muslim religious identity or resolving religious disputes but to instead identify and confront those aspects of sectarianism that are negative, exclusionary, or violent. It is therefore important to explore avenues for diverse religious communities to co-exist in a peaceful manner and to provide the space for greater religious pluralism in public spheres. Doing so would acknowledge sectarian identities and differences and explore the legitimate ways in which diversity can exist and be appreciated within the Muslim world.

Payam Mohseni is the Director of the Project on Shi'ism and Global Affairs at Harvard University's Weatherhead Center for International Affairs and a Lecturer in the Department of Government at Harvard University.

Mohammad Sagha is a postdoctoral Division of Humanities Teaching Fellow at the University of Chicago and an Associate at the Project on Shi'ism and Global Affairs.

For the Spanish translation of this article, click here.

[1] According to these studies, over 90% of terrorist attacks carried out by Muslims were from these Wahhabi or Salafi-linked groups; Fareed Zakaria, “How Saudi Arabia played Donald Trump,” The Washington Post, 25 May 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/global-opinions/saudi-arabiajust-played-donald-trump/2017/05/25/d0932702-4184-11e7-8c25-44d09ff5a4a8_story.html. Also see: Salem Solomon, “As Africa Faces More Terrorism, Experts Point to Saudi-spread of Fundamentalist Islam,” VOA, 20 June 2017, https://www.voanews.com/a/africa-terrorism-saudi-fundamentalist-islam/3908103.html

* This article is taken from a larger report published by the Harvard Kennedy School Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs' Iran Project: Engaging Sectarian De-Escalation: Proceedings of the Symposium on Islam and Sectarian De-Escalation at Harvard Kennedy School. Edited by Payam Mohseni. 8/25/2019. Cambridge, MA, USA: Harvard Kennedy School Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs.

Image Captions (from top to bottom):

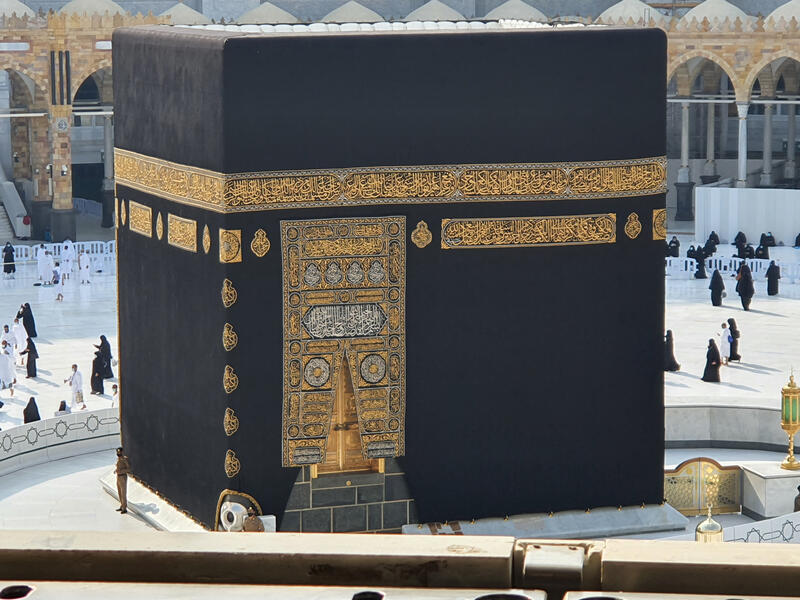

The Holy Ka'ba in the Great Mosque of Mecca. 4 Dec. 2020. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Two U.S. Marine Corps M1 Abrams tanks patrol the streets of Baghdad, Iraq. 14 April 2003. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Masjid an-Nabawi in the city of Medina. Dec. 2018. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.